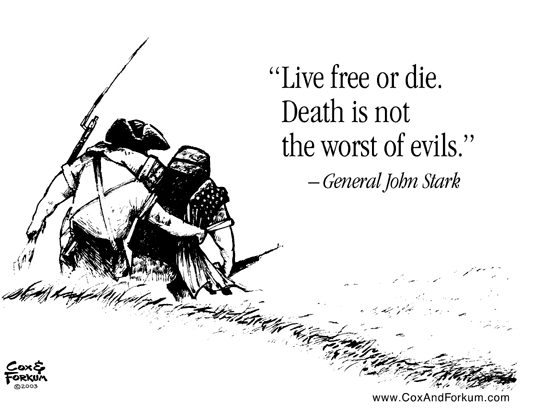

I posted the following editorial cartoon over at one of my other blogs:

While some will I’m sure object to the quote in the cartoon above, I will argue that the quote itself is reflected in much of the Book of Mormon, as well as in LDS history, though not always in the way one would think.

FIrst, the easy part. The message that “death is not the worst of evils” pervades the Book of Mormon. A long series of prophets, starting with Lehi, risk their lives in order to deliver God’s word; some, such as Abinadi, die unpleasant deaths as a result. Likewise, believers risk — and in some cases lose — their lives for their beliefs. The women and children converted by Alma2 and Amulek in Ammonihah are thrown alive into a pit of fire; Alma2 notes that “the Lord receiveth them up unto himself, in glory.” (Alma 14:8-14). The people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi allows themselves to be killed rather than take up weapons or renounce their faith; “and we know that they are blessed, for they have gone to dwell with their God. . . . Therefore, we have no reason to doubt but they were saved.” (Alma 24:20-26). The Book of Mormon also notes the tragedy of those who die unprepared to meet God (Alma 48:23), and several of the prophetic discourses in the Book of Mormon (notably Jacob and Alma2 ) stress the importance of being prepared to meet God (via death) at all times.

Likewise, LDS history and doctrine — particularly up through the end of the 19th century — strongly emphasizes that what matters is not death but our state at death: “And it shall come to pass that those that die in me shall not taste of death, for it shall be sweet unto them; and they that die not in me, wo unto them, for their death is bitter.” (D&C 42:46-47) We honor our pioneers, particularly those who died during persecutions and the long trek out to the Salt Lake Valley, and we seek to express our own willingness for such sacrifice when we sing

And should we die before our journey’s through,

Happy day! All is well!

We then are free from toil and sorrow, too;

With the just we shall dwell!— “Come, Come Ye Saints” by William Clayton

Second, I would argue that the sentiment “Live free or die” is reflected through much of the Book of Mormon as well, as well as in LDS history, though with perhaps at times with a different meaning than usually suggested by that phrase.

The classic interpretation in and of itself is quite clear in the Book of Mormon. The attempt by Amalickiah to reinstate a kingship by force (with support of the lower judges — so much for ‘democracy‘) over the Nephites leads Moroni1 to raise his famous title of liberty (cf. Alma 46). Amalickiah flees over to the land of Nephi, where his coup in turn against the Lamanite king is successful, and he stirs up the Lamanite nation against the Nephites, leading to this observation by Mormon (who also brings up the ‘unprepared for death’ theme again):

But, as I have said, in the latter end of the nineteenth year, yea, notwithstanding their peace amongst themselves, they were compelled reluctantly to contend with their brethren, the Lamanites. Yea, and in fine, their wars never did cease for the space of many years with the Lamanites, notwithstanding their much reluctance. Now, they were sorry to take up arms against the Lamanites, because they did not delight in the shedding of blood; yea, and this was not all—they were sorry to be the means of sending so many of their brethren out of this world into an eternal world, unprepared to meet their God.

Nevertheless, they could not suffer to lay down their lives, that their wives and their children should be massacred by the barbarous cruelty of those who were once their brethren, yea, and had dissented from their church, and had left them and had gone to destroy them by joining the Lamanites. Yea, they could not bear that their brethren should rejoice over the blood of the Nephites, so long as there were any who should keep the commandments of God, for the promise of the Lord was, if they should keep his commandments they should prosper in the land. (Alma 48:21-25)

Still, this same book of Alma tells of the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi, who were perhaps the most righteous people in all of Book of Mormon history — who willingly died rather than take up their swords against their fellow Lamanites. This they did rather than violate their covenant with God that they would never take up weapons of war again, because of their previous “sins and many murders”, swearing that “rather than shed the blood of their brethren they would give up their own lives” and that they “would suffer unto death rather than commit sin.” (Alma 24:6-19).

Likewise, with rare (and usually unproductive) exceptions, the Latter-day Saints chose to move along — from New York to Ohio to Missouri to Illinois to the Rocky Mountains, with resultant hardship and death — so that they might live free to practice their religion. While the Doctrine & Covenants does contain the “Lord’s law of battle” — which justifies battle only after three efforts at peaceful settlement have been rejected (cf. D&C 98:34-38) — the few instances of armed resistance by Latter-day Saints usually just made things worse.

Still, it is the children of the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi — those who become Helaman’s two thousand “stripling warriors” — who turn out to be the most effective fighters in all the Book of Mormon. And their motivation? Here’s what Helaman1 writes to Moroni1 about leading them into battle for the first time:

Therefore what say ye, my sons, will ye go against them to battle?

And now I say unto you, my beloved brother Moroni, that never had I seen so great courage, nay, not amongst all the Nephites.

For as I had ever called them my sons (for they were all of them very young) even so they said unto me: Father, behold our God is with us, and he will not suffer that we should fall; then let us go forth; we would not slay our brethren if they would let us alone; therefore let us go, lest they should overpower the army of Antipus.

Now they never had fought, yet they did not fear death; and they did think more upon the liberty of their fathers than they did upon their lives; yea, they had been taught by their mothers, that if they did not doubt, God would deliver them. And they rehearsed unto me the words of their mothers, saying: We do not doubt our mothers knew it. (Alma 56:44-48)

Still, the Book of Mormon’s major theme hearkens more back to the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi: spiritual freedom (even if it leads to death) is better than life (if it leads to spiritual death). “Live free or die” gets a new meaning in the light of passages such as these:

Wherefore, men are free according to the flesh; and all things are given them which are expedient unto man. And they are free to choose liberty and eternal life, through the great Mediator of all men, or to choose captivity and death, according to the captivity and power of the devil; for he seeketh that all men might be miserable like unto himself. (2 Nephi 2:27)

“Live free or die” is literally the choice before us, while “Death is not the worst of evils” is a reminder of what really matters in our mortal — and eternal — lives. There are causes worth dying for, and there are outcomes to our choices that are worse than death. Both things worth keeping in mind. ..bruce..